Well, it’s been a while since I wrote — so far in 2022 I’ve mostly been focussing on my freelance work (hire me 😉) and having some surgery which rendered me mostly out of action for a month or so.

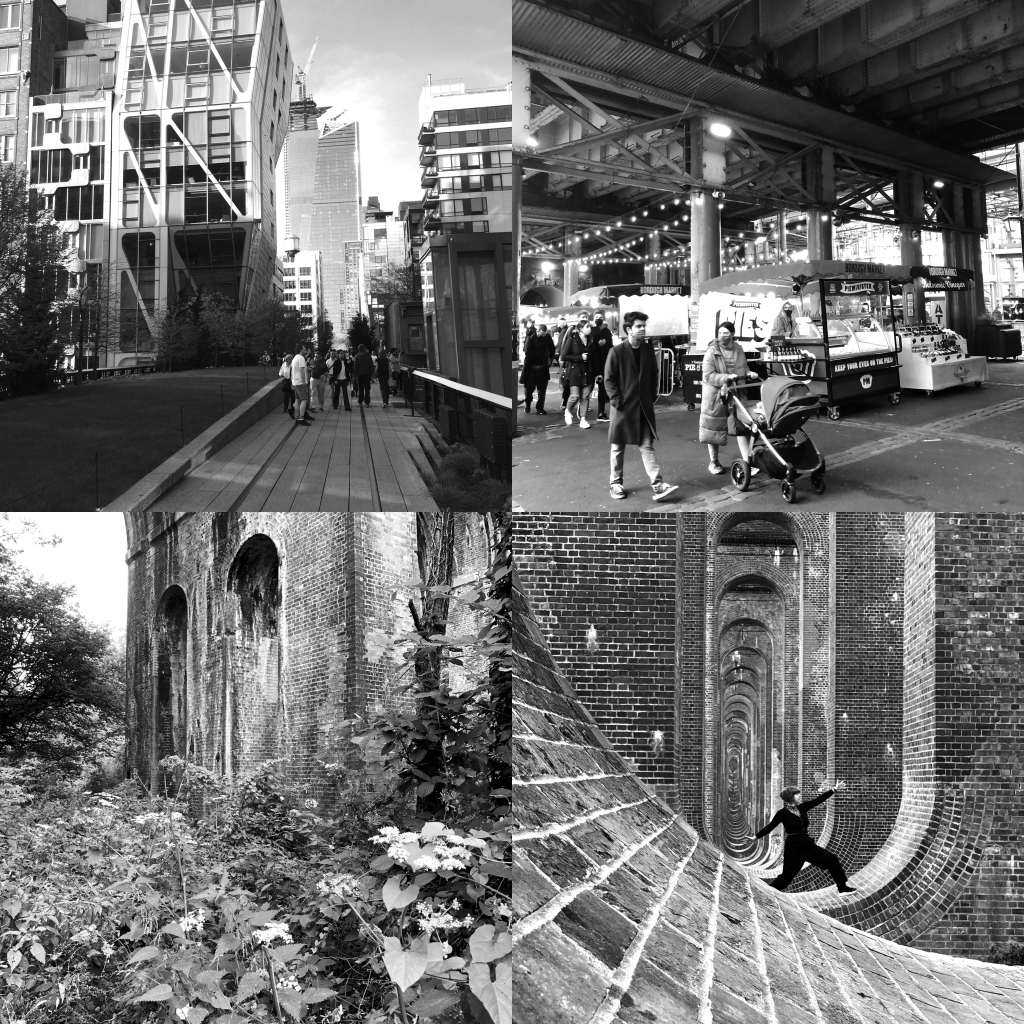

I am still thinking about ways to pursue my research further in future, and was delighted to have the opportunity to get involved with an ‘ExploreStation’ workshop — the perfect chance to get my thinking cap on once again about the future of the UK’s railway network, and how its infrastructure impacts on the communities around it.

In fact, these workshops pretty perfectly hit upon the venn diagram of ‘Emma’s interests’, as they were also focussed around the notion of ‘co-design’ — allowing communities to play a part in the conception and design of the spaces they will be using.

About the workshops

So, back to the start. What are these workshops about and who are they organised by?

A few years ago, Network Rail (the body who manage and run the UK’s railway infrastructure), decided to embark on a scheme to radically re-envision how the UK’s small to medium sized stations (that’s four out of every five railway stations in the UK) are built and renovated.

At present there is little consistency in terms of the design and construction of these stations, which — I would argue — is part of their charm. However when it comes to long term maintainence, consistency of experience, and (though some would argue this matters less) overall brand integrity of the UK’s railways, the current approach leaves a lot to be desired. Not to mention the environmental impact of their buildings and construction.

Of course, a one-size-fits-all ‘new station template’ wouldn’t work either — stations are situated in very different spaces and locations. Some have architecturally important buildings which should be kept. Plus there isn’t the budget to ‘tear it down and start again’ on every small to medium sized station in the UK. What Network Rail want is a ‘kit of parts’ so that when aspects of a station need refreshing or replacing, it can be done in a consistent way.

They launched a competition for architects across the UK and around the world to enter, in which they were challenged to come up with a solution to these problems. In May 2021 it was announced that 7N Architects, who are based in Edinburgh, had won, with their ‘HUB’ station design proposal. You can read/see a bit more of this here.

However, this wasn’t where the project ends. Network Rail commissioned the Design Council (A charity who are effectively the UK government’s advisors when it comes to any matters of design), The Glass House (A charity that supports organisations with involving the community in their design process), Digital Urban (who help build 3D models of places to give people a better understanding of spaces and places), and Commonplace (A ‘citizen engagement platform’) to figure out how best to involve the general public in developing these designs further.

At the heart of their quest for knowledge from us, the general public, was how these stations could become more than just conduits for getting on and off a train, and actually become vital community hubs, which sit at the heart of the places they connect. An interesting challenge given that not all of these stations actually are geographically at the heart of their locations, and that large swathes of the population rarely or never use the railway network!

These questions also tie into a lot of my research and thinking (particularly at the early stages of my MA project, like my ponderings of Clapham Junction station) around the potential of stations to be more than just stations. Suffice to say, I was super excited to take part in this series of workshops!

The workshops so far have taken place in two phases. The first round (which I didn’t know about!) happened last November/December, and asked small groups to feedback on 7N’s initial design proposals. (As an aside, really pleased to see that these workshops have been run in cities across the country, NOT all, or indeed, at all in London!)

We weren’t privy to the detail that was gleaned from these workshops, but one thing which was mentioned were concerns about light pollution from the (previously very glowy) clock tower design, as well as feedback about the neccesity of toilets being situated outside the gateline, if they want these stations to become true community hubs. (Good feedback which I would agree with!)

With revisions made by 7N, these next workshops were designed to glean more feedback specifically about community use of the station spaces. I attended the third of three workshops in Brighton, on May 25th, 2022.

The workshop

The workshop was located at my old undergrad university campus — the University of Brighton’s ‘Grand Parade’ building. It was slightly strange to be back for the first time since my graduation in 2010!

All attendees were given a lovely brochure about the workshops and the station proposals, which I found very well thorough and well put together, and helpful to browse while we waited to start.

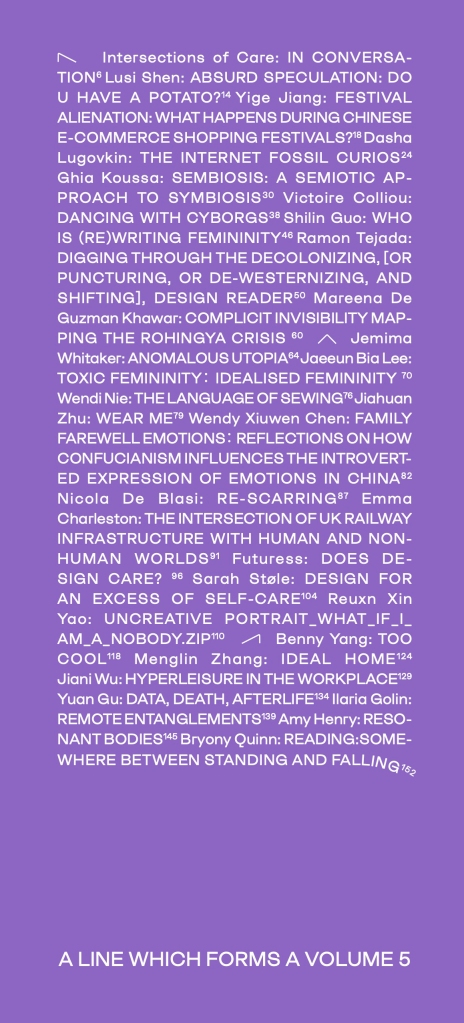

The last image above offers a good summary of what the early workshops identified as important in the HUB station design. These were that the station should:

- support existing and new communities

- understand and embody local character and heritage

- provide consistent quality of space for service and passengers

- establish connections between town centres and high streets

- celebrate and improve the quality of green/open space

- facilitate inclusive travel

- support and better integrate model transport (by which I assume they mean buses and trams)

- address climate change

- ensure longevity (I assume this means ‘of the station facilities’, but if it can somehow help MY longevity too, then bonus 🙂

The workshop opened with a presentation of the proposals so far. I haven’t been able to find a thorough version of this online, but this design council article offers a reasonable summary.

The station proposals are, as mentioned, a ‘kit of parts’. This includes the area directly outside the station (described by them as the ‘welcome mat’, which I quite liked), the canopies over the platforms, as well as modular spaces allowing for all kinds of different applications, from station-related stuff like waiting rooms, toilets, ticket offices and staff space, through to more community minded stuff like shops, cafes, and other multi purpose spaces. A key part of the design is the iconic ‘clock tower’, which would make the station visible from farther afield, and is designed to lightly glow as trains pass.

I feel like this should be a space where I go hard on critique of the designs, but actually, for the most part, I felt really positive about them. I was impressed by their thoughtfulness around use of materials, and the ‘build less’ mindset. Much of the station would be constructed from wood, which is both more environmentally friendly than many other materials, and due to its lighter weight, reduces the need for large foundations (lots of concrete). I was also impressed that they offered an explanation of why they had NOT used some popular environmental choices like rainwater collection (actually less environmentally friendly due to energy used in pumping and space/energy used for storage) and green roofing (little actual positive environmental impact and uses up space that would be better used by solar panels).

The only downside of the ‘build less’ approach was that I (and a number of other workshop participants) shared concerns about the Great British weather — if these stations are to meaningfully become community hubs, they must offer sufficient shelter to offer comfort year round, not just in the balmier summer months that the visualisations appear to depict.

I was also impressed by the modularity of the systems — in settings where, for example, a station building is beautiful and historically valuable, the modern platform canopy design, clock tower and ‘welcome mat’ concoruse area could still be deployed around it, lending the station a feeling of consistency, while still not losing its unique local character. Another nice touch was for the clock towers to be constructed from local materials, so that they don’t feel out of keeping with their surroundings.

To round off that section of the workshop, we were asked a series of quick fire questions (and given a worksheet to answer them on), about whether we understood the plans, and whether we agreed with various aspects of them. It was a good way to give our feedback quickly, and in a way which didn’t allow any voices to dominate. (I am not a fan of workshops which rely on the ‘any volunteers to speak’ approach, as they can end up being over-long and often don’t allow a range of voices to be heard.)

But what about the teens

The second half of the workshop saw us divided into small groups of four or five, and asked to consider one particular area of the station in detail — and how that area could be used by the community. We were given the ‘welcome mat’. We initially pursued two areas of interest. The first, somewhat predictably, was community gardening, which feels like a big buzzword (/buzz idea?) at the moment. And with good reason — gardening is a wonderful collective activity which offers rewards for both participants and the environment. However, so often these sorts of schemes are hatched with little thought to their long term maintainence, or how community dynamics will actually work in practice. The most successful community gardening schemes tend to be those initiated and run by communities themselves, rather than those launched upon communities from on high. (I have been doing some pondering/work around this under one of my other professional hats, which I may write more about here soon!)

The other idea we discussed was space for teenagers. Railway stations and other transit hubs have often been spaces where young people congregate, due to their freedom of entry, provision (sometimes) of facilities like toilets and benches, and their often mostly un/under supervised nature. This use isn’t without its problems. Large groups of teenagers can be intimidating for other users of stations, and they do, at times, fail to treat said communal facilities with respect. We wanted to ask the question of how a space could be created that welcomes teenagers, offers them comfort, safety, and a space to be themselves, while also not jeopradising the other uses of the station and its surrounding spaces.

After discussing these ideas for 15 minutes or so, we were provided with an exciting and somewhat unexpected collection of art supplies, and asked to pick one of our ideas and visualise it. We opted for the space for young people (and I’m glad we did, as I think three of the other groups went for some variation on community gardens!)

We only had 15 minutes to put together our final vision, which quite obviously wasn’t long enough to do anything justice, but we tried our best.

We rather trendily called our concept the ‘teen hub’ (I’m sure the teens will come flocking with a cool name like that), and used our large sheet to discuss a number of ideas.

- What kind of space would feel comfortable for young people to spend time in? We settled on the idea of a stepped outdoor theatre style space, which has the added bonus that it could occasionally be requisitioned for community performances. But most of the time, it just offers a seated, slightly sheltered from the wind space with lots of different areas and aspects for groups of teenagers to mingle in. (The white dough was my attempt at an outdoor stepped theatre but it kind of looks like creepy teeth…)

- We were keen on the idea that this space be overlooked, but not observed. Some way of offering young people a space of their own, where they feel able to relax and socialise, but also not a totally lawless area. One of our group suggested further shelter/seclusion be provided by Mashrabiya style screens, a feature of middle eastern/islamic architecture which offers both privacy and visibility all at once. (The red dough was one of the other group members attempt as a mashrabiya)

- We felt that it was important that the welcome mat area didn’t become a space ONLY for young people. We pondered on the idea of other events frequently happening adjacent to the stepped theatre area, like farmers markets, pop up vendors, and in smaller communities, that this could be the space where the library van, bank van, blood donation van etc. pitch up. This would ensure a constant flow of people around the space, while the mashrabiyas and lowered seating area would still offer the teenagers the degree of privacy and seclusion which they want.

- Of course everyone knows you can’t just say to teenagers ‘this is your space, use it’. We discussed what other incentives (beyond simply creating a space which hopefully offers a desirable seating/sociability format) would be needed to persuede ‘the kids’ that this was where they wanted to be. Perhaps the youngest member of our group (I’d guess a man in his mid twenties) emphastically said ‘bubble tea’. I also suggested ice cream. The conclusion was, venues selling cheap, tasty teenage treats, that are non-alcohol focussed and stay open late. Bubble tea, Ice Cream, whatever it might be. Capitalism is none of our friend, but when thinking about the existing frameworks we live in, offering desirable goodies for sale with long hours and relatively cheap prices, seems like a tantalising prospect for building community spaces which include all ages of the community, not just adults.

- Of course, while there might be shops/cafes and other spendy places, at the heart of a community space should be FREE amenities. These would include toilets, a water fountain, and we also did touch on surrounding the lowered seating with fragrant but hardy plants, some of which would be forageable.

Of course, in the time we had, our plans couldn’t possibly address all questions/concerns. Our space is still open to rainfall, even if it does try and be a little sheltered from the wind. Is that good enough? Does taking things under cover raise other issues around access and safety? Who maintains the fragrant planting? Is it network rail, or the community? If stations aren’t at the centre of their locations, how do you persuede your bubble tea vendor that this is a good place to set up shop? (We did discuss all retail being on a pop up basis to start with, with regular schedules, so that, e.g. ‘Friday night until late is Bubble tea night’). Plus loads more questions beside.

But it was good to try and tackle a tricky issue — as someone who grew up in a rural area where transit hubs were absolutely social spaces for teenagers, and often not in a particularly positive or healthy way, how could this situation be turned on its head? When thinking about these new small-to-medium stations as community hubs, it’s vital that they are for ALL of the community, not just middle class white people aged 25 – 45. Our attempt to address the 12 – 18 demographic felt like an interesting challenge, though of course, as a bunch of adults, we are falling into the trap I’ve criticised, of attempting to design for those not ourselves. A meaningful consultation/idea generation session on this idea would include not just 12 – 18 year tolds, but 12 – 18 year olds from the specific community where the plans were being discussed.

All of the groups presented their proposals, and (though there were a number of community gardens), it was exciting to hear how different people had thought things through. (and with much better use of pipecleaners than us). These workshops were directly facilitated by The Glass House, who recorded our little mini presentations, and collected all of our worksheets and concepts afterwards, and will presumably be back in their glass house (?) wrangling all of this (and the other workshops) into some kind of presentation to 7N and Network Rail in a few months time.

Afterthoughts

Overall I really enjoyed the workshop. I am glad that Network Rail have decided to try and consult more widely than just within the design/architecture community, and other ‘experts’. The challenge, of course, is engaging with communities who maybe wouldn’t come to hear about these workshops. (Like for example, the 12 – 18 year olds we were attempting to design for). I am not sure how they were promoted (I heard about them via a design council person I follow on Twitter), but the issue is that they will always be inherently self-selecting. From what I could tell, most people who came were either transit nerds, design nerds or both (me). How can we ask these kinds of questions of people who are none of these things? People who might think they’re not interested in public transit at all?

I was really impressed by the Glass House’s overall approach, and do feel sure that they are asking these questions of themselves and their collaborators too.

I’m excited to see where this project goes next, and hoping I can find other ways to be involved!