Each year, the MA Graphic Media Design cohort publish a book of critical design writing, forming part of a series called ‘A Line Which Forms a Volume’. The publication is made up of contributions from some members of the course, as well as external contributors. A group of students curated, edited and designed the entire thing to a scarily short deadline (of which I was not one — I had more than enough on my plate with trying to hold down work alongside the course!) — the final outcome is, as always, very impressive (if a little dense in places…)

I was delighted to be selected a one of the contributors, after pitching a place about the co-existence of human and non-human worlds in the context of railway infrastructure.

The theme of this year’s ALWFAV is ‘Leaning’, and structures of care. Taken from the formal descriptive text written by the curators:

“ALWFAV 5 explores how the act of leaning on, with and into a research topic can be regarded as a form of care for the complexities of contemporary society. We ask: ‘Who are we, and who do we care for?’

Bringing together contributions from Bryony Quinn, Intersections of Care, Futuress, Ramon Tejada and the MA GMD participants who share their emergent design research, ALWFAV 5 approaches the idea of leaning from a particular perspective—the encounter between care and radical transparency in design research. By using graphic design as a critical tool for investigation and divulgation, we build physical and conceptual support structures that provide publics with a route into the research areas we contribute to.

The publication […] offers space for our contributors to share how their design practice correlates with the notions of leaning through care and radical transparency.”

I am pleased to share my piece for the book in full below.

The intersection of UK railway infrastructure with human and non-human worlds

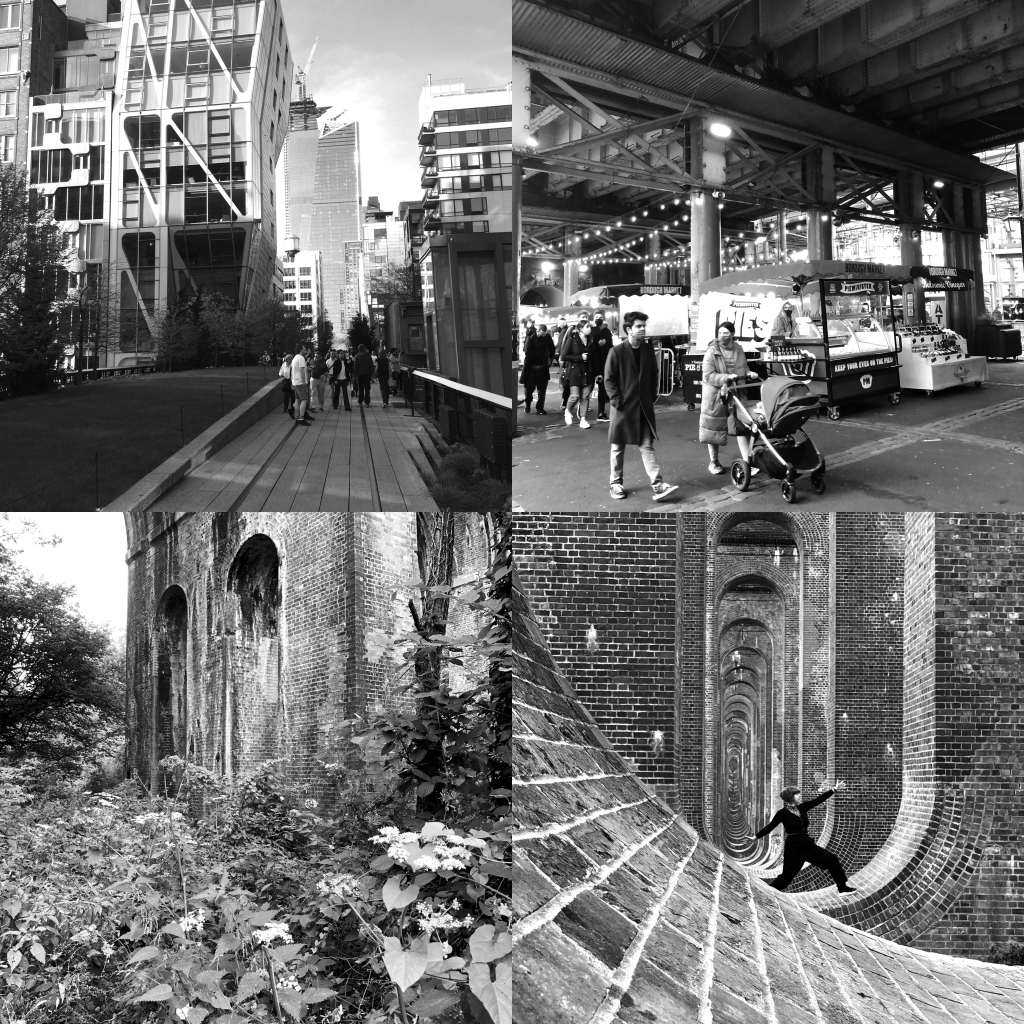

Clockwise from top left: New York’s High Line Park / Borough Market, which is situated around and underneath railway lines near London Bridge / The Ouse Valley Viaduct, rural railway infrastructure which is frequently visited as instagrammable artefact / A less visited viaduct near Burgess Hill which has been claimed by nature

Across the UK run many complex networks of infrastructure, but perhaps one of the most visible and physically spacious is that of our railways. It intersects with countless communities and neighbourhoods, both dividing and connecting, as viaducts, cuttings, bridges, arches, tunnels, and station buildings sprawl across our cities and countryside. Yet for many people, despite their scale, these structures tend to fade into the background of their day-to-day experience.

During the 19th century when the railways first started to spread across the UK, competing providers raced to secure the best routes across the country, particularly into London, resulting in a dense web of structures (especially south of the Thames) which have left a lasting mark on the access, layout and function of the neighbourhoods which they pass through.[1]

There is now a huge range of human activity beyond the direct operation of the railways which leans on the infrastructure of the network. Throughout the UK there are approximately 5,200 railway arches which play host to businesses of all kinds. [2] Railway stations are also home to many small and large companies — often food and drink outlets, but with countless other more creative examples, like the Green Door Store music venue in Brighton which sits in the bowels of the station’s sloping underground areas, or the tiny ‘Northern line’ antiques store on the quaint platforms of Knaresborough station, in Yorkshire.

And these are just examples which make use of still-functional infrastructure. When railways and their surrounding facilities have fallen into disuse, what’s left behind is often repurposed for alternative human needs — one of the most famous examples of this is New York’s much-loved [3] High Line park, which runs along a disused railway line and offers striking views across the downtown Manhattan streets it passes over. There are plans to recreate a similar scheme in London with the upcoming Camden High line. Nearby in Chalk Farm, an old train turntable building has been transformed into the iconic ‘Roundhouse’ cultural venue. Even when disused railways are left to totally crumble, the spaces they leave behind can be highly functional, due to their straight ‘as the crow flies’ routes, with former railway routes often transformed into footpaths or cycle lanes. [4]

In my research I have been following the London to Brighton railway line, and exploring the past, present and future of the route, the connections it fosters between these two diverse cities, and the spaces it creates and comes into contact with as it travels. [5]

I often found myself imagining potential uses for disused or under-utilised spaces formed by railway infrastructure from my own perspective as a designer and urbanist. I was initially tending to approach them from a very human-centric, capitalistic focus, even where I thought that I was striving to push back against such ideas. (A pop up market of independent traders is still a capitalist notion, albeit one which prioritises small business over big).

Faced with the challenges of a rapidly changing climate and uncertain urban futures, what would it mean to step even further away from our human-centred perspectives of space, particularly in urban conurbations? How could we creatively show care for these void spaces we have created in ways that move beyond human needs? In coming to an understanding of place and space from a non-anthropocentric perspective, we can even further recognise the value of our railway infrastructure network as a support structure for both human and non-human needs, growth and life. (‘Non-human’ sometimes considers robotics and AI, but for the purposes of this piece refers to the non-human in the natural world [6])

Heightened uptake of public transit is an essential tool in our fight against climate change — this is the clear headline. However, it is also crucial to recognise the value of the wildlife corridors which are formed by railway lines — albeit ones which are controlled and managed by Network Rail to facilitate the clear and smooth movement of trains, but nonetheless, wild spaces of vital importance, and home to an incredibly diverse variety of our non-human neighbours.

Still, I often see empty spaces created by railway infrastructure as filled with potential for human activity. But I continue to try and ask — how can we create spaces that expand past the imagination of what might please or help humans alone? How can we foster the creation of non-anthropocentric worlds of varying scales and varieties which cease to put capitalist human ideas first? In coming years the balance between human and non-human needs may become increasingly fraught, as our changing climate causes global migration of both people and animals [7]. But by acting now, and by acting with imagination, care and mindfulness, the spaces created along our railway corridors may be a small but crucial contribution to salvation for all of us, and a more balanced, thriving existence between neighbours of all kinds.

- Jenkins, S. (2021) (p.20) Britain’s 100 Best Railway Stations. Reprint edition. London, UK: Penguin.

- The Arch Co (no date) The Arch Company. Available at: https://www.thearchco.com/ (Accessed: 4 August 2021).

- Higgins, A. (2014) New York’s High Line: Why the floating promenade is so popular – The Washington Post, Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/new-yorks-high-line-why-the-floating-promenade-is-so-popular/2014/11/30/6f3e30cc-5e20-11e4-8b9e-2ccdac31a031_story.html (Accessed: 4 August 2021)

- ‘Our History | Railway Paths | public routes, roads and paths suitable for cycling, walking, horseriding and wheel-chair use’ (no date). Available at: https://www.railwaypaths.org.uk/our-history/ (Accessed: 12 May 2021)

- Charleston, E. (2021) LDN – BTN. Available at: https://ldn2btn.uk/ (Accessed: 24 October 2021).

- Nonhuman Rights Project (no date). Available at: https://www.nonhumanrights.org/ (Accessed: 24 October 2021).

- Anderson, B. (2021) (de)Bordering the human and non-human worlds – Migration Mobilities Bristol. Available at: https://migration.bristol.ac.uk/2021/06/08/debordering-the-human-and-non-human-worlds/ (Accessed: 24 October 2021).